Harvesting History

The first Collins foresters such as George Flanagan and Wally Reed were trained in and strong proponents of selection silviculture applied to the Sierran mixed conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascade Range. Based upon their knowledge and philosophy, the CAF has been managed under single tree selection silviculture since the inception of commercial logging in 1941. This management philosophy has been faithfully carried on by subsequent forest managers and staff. Instrumental to implementation of selection silviculture was development of a tree risk rating system, which gave rise to the Almanor Tree Classification System. Under this system, trees are classed based upon their crown characteristics and placement within the stand.

Since harvesting first began in 1941, prescriptions have been light single tree selection entries removing 15-45% of the volume per acre at each entry, with a variable harvest cycle of the property of about 15 years. The first harvest cycle was called the “high risk” entry with the principal focus being on light sanitation to capture mortality and control bark beetle losses. Usually the cut trees were Almanor 7, 8, or 9’s with evidence of impending death within 10 years. Due to lack of markets for the other species, only pine and Douglas-fir were harvested in the first cutting cycle, where the typical harvest entry captured 6,000 board feet and two to four trees per acre.

The second harvest cycle, called the “harvest cut” began in the late 1950’s. In this cycle, which extended more than 20 years to 1981, the focus was on a planned reduction of over-mature trees and non- growing trees (Almanor Classes 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and damaged, diseased or severely suppressed trees). Though many thrifty, larger and older pine trees were retained in order to provide parent stock for natural reproduction and stocking purposes. Harvest cuts were, again, by single tree selection. Capture of mortality remained an important factor in the harvest design.

The third cycle, labeled the “transition cut” began in the early 1980’s. Here, the focus was on stand sanitation and mortality capture with a continuation towards a more balanced distribution of age/size classes within stands, and to encourage pine regeneration where possible. Harvest volumes ranged from 4 to 7 thousand board feet per acre.

By the late 1980’s, a shift in emphasis occurred with respect to the planned elimination of over- mature trees. At that time, it was determined that the owners’ objectives were best served by retaining a component of older, mature pine trees, indefinitely.

Concurrently, a shift in perspective occurred with respect to the retention of “highly defective” trees that possessed value with respect to wildlife habitat and the aesthetic character of the forest. This transition in outlook is ongoing, today, and has been formalized by the CAF Sustained Yield Plan, dated January 1998.

By 1997, most of the property had been covered in the relatively light Transition Cut. Currently CAF is well into its fourth harvest. The overall goal of this harvest is to manage the forest in such a way as to increase and maximize the sustainable growth of the timber resource and the financial return to the owners while maintaining and enhancing all of the other forest values including wildlife, aesthetics, clean water, soil productivity, and recreation. This should be accomplished without forfeiting any potential opportunities for future generations of owners or managers.

Future harvest cycles will continue to balance the multiple objectives of the forest; providing a regular annual harvest tied to actual periodic growth, enhance the pine component within the forest species mix, enhance the wildlife attributes of the forest, and maintain the high aesthetic characteristics of the forest through the retention a multi-canopy structure, including the maintenance of larger trees throughout CAF.

Harvesting on Other Private Lands

Private lands within the area, other than Collins Almanor Forest, will likely be managed in the foreseeable future as they have been in the recent past. Timber harvest should primarily be of a selective, uneven-aged nature and clear-cutting should constitute a relatively minor portion of the activity.

On these other private properties, intensive uneven-aged management typically results in stands that are maintained in the California Wildlife Habitat Relationship 4M (11-23” DBH and 40 –59% canopy cover) to 4D (11-23” DBH and >60% canopy cover) condition. Selective harvest generally occurs when canopy coverage is over 60 percent and the quadratic mean diameter of the stand is in the 11 to 23 inches DBH range. Harvest tends to reduce the canopy cover below 60 percent and take trees of various size. Hence, a 4D stand typically turns into a 4M after harvest, which will eventually grow into a 4D stand again. This cycle could theoretically be sustained indefinitely, resulting in major amounts of these forest in either 4M or 4D conditions.

Wildfire may affect large portions of these private lands, but it is not likely. One reason is that the terrain is relatively gentle and road systems are extensive, making fire fighting very effective. In addition, intensive fuels management has been conducted over large areas within the area during the past decade, using biomass thinnings. Where they do occur, any large fires would result in early seral habitats. Existing early seral habitats, including plantations created in old burns, will tend to move toward mid-seral conditions as shrubs become mature and decadent and conifers increase in density and become larger shading out the shrubs.

Existing late seral stands, though limited in extent, will likely be managed in a similar manner to the other commercial forest stands, as mentioned above. In summary, non-CAF private land management, within the area, will consist of a preponderance of mid-successional habitats with a likely trend toward declining amounts of later seral types.

Harvesting on Public Lands

Much of the area around and scattered within CAF consists of public lands, administered by the USDA Forest Service. Future forest management on these lands, although somewhat uncertain due to current political fluxes, will likely be considerably less intensive than on private lands. Emphasis will likely follow these themes: First, the protection of large trees and forest structural characteristics thought to be present prior to European settlement and fire exclusion. Second, the management of fuels to reduce the likelihood of catastrophic fires. Fuels management may be intensive in scattered bands or zones, resulting in shaded fuel-breaks and the use of group selection harvesting up to two acres in size per Quincy Library Group recommendations. Third, the maintenance or enhancement of ecological systems in riparian habitats.

Spotted owl Pair Activity Centers (PACs), 1,000 acres in size, will be maintained around existing owl pairs, including a 300 acre nest core, a contiguous replacement core area, and 400 acres of additional stands in suitable condition. In addition, late successional, old growth, and forest carnivore reserves will be scattered through the public lands (see Lassen National Forests Resource Management Plan, for the location of these areas). The extent of late seral stands will likely increase over the next 50 years, perhaps on the order of 50-100 percent according to the CASPO Draft Environmental Impact Statement; 1995.

In summary, the future emphases on public lands will likely result in an increase in late seral stands and a moderate increase in early seral stage areas within the area. Harvesting will predominately be of an uneven aged silviculture using individual and group selection systems, with relatively few clear cuts.

Harvesting on CAF Lands

Future CAF management will place increased emphasis on afforestation efforts along with the retention of sizable trees, decadent trees, snags and large woody material throughout the ownership. Levels of late seral habitat elements that will produce moderate to high populations of wildlife species dependent upon these elements will be retained in functional late seral stands.

These future CAF strategies will have a tendency for a maintenance of functional later seral conditions, especially in WLPZ’s, while continuing to provide for some early seral habitat, unless unforeseen large wildfires occur which will create new early seral types.

Assessing Forest Management Silvicultural Requirements

Developing the current timber management prescriptions for the Collins Almanor Forest began with a series of discussions and field tours in 1995. The discussions initially focused on the management history and the three prior harvest cycles and what the present day forest looks like, given the past fifty plus years of harvesting.

The next step was to evaluate the current forest condition and identify potential silvicultural concerns regarding future management. One of the foremost concerns that emerged was species composition and the question of as to the best species and diameters to harvest in order to maintain a strong pine component and meet other silvicultural goals. Also, how will the rate of harvesting in the overstory affect seedling establishment, survival and growth? An additional concern is maintaining the distribution and quality of large (>24”) trees for the increased value of the timber products as well as ecological, aesthetic, and wildlife values. Other concerns relate to maintaining a high level of volumetric growth, maintaining desired canopy levels, and attaining varied degrees of late successional attributes.

These issues will be addressed in the near future utilizing the “Forest Projection and Planning System”, or “FPS, developed by the Forest Biometrics Research Institute.

Logging Methods

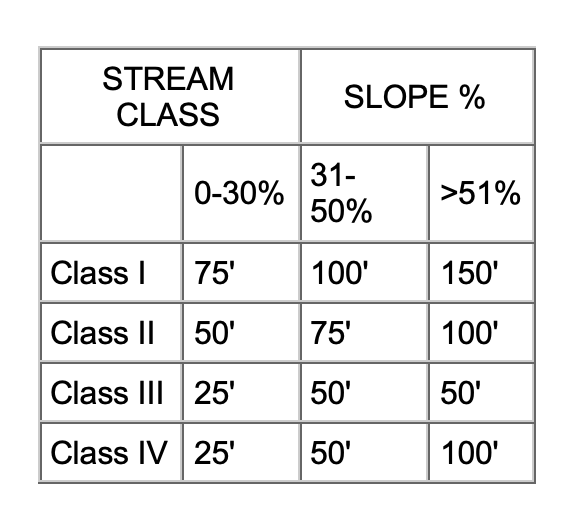

Historically, the entire CAF was logged with ground-based equipment using either track or rubber tire skidders. Within the past 20 years, cable yarding systems have been employed, particularly on the steeper slopes within the Wolf Creek block. Under the Plan, generally, only cable-based skyline yarding systems will be employed on slopes in excess of 45%. On areas of high surface erosion and mass wasting potential, the slope break between ground and cable systems may be lower.

Upslope Harvesting Constraints

Watershed analysis and field observations confirm that the selection silviculture system employed on CAF is not measurably contributing to adverse cumulative watershed effects. Accordingly, no particular upslope mitigation is called for relative to the avoidance of cumulative effects.

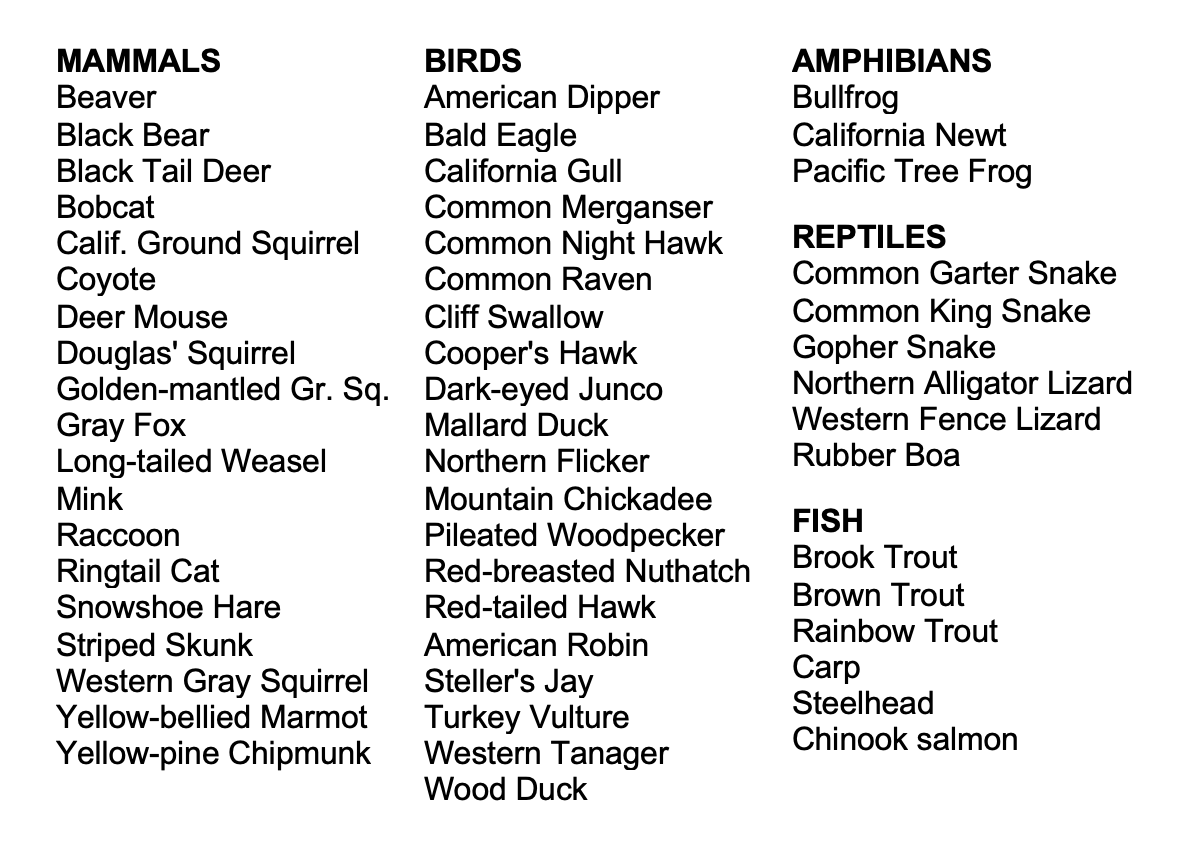

Even though CAF has always had an aggressive salvage campaign and CDF required snag falling in the recent past, the exclusion of fires and the increase in the number of true firs has created a situation where there is an adequate level of wildlife trees to accommodate the species requiring them. However, these numbers are constantly monitored and if they are deemed to be declining, adjustments to management will be made.